Therefore he is the mediator of a new covenant, so that those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance, since a death has occurred that redeems them from the transgressions committed under the first covenant. | Hebrews 9:15

After service Sunday, someone asked me about why, in a sermon about the covenants, I never mentioned the New Covenant. Why focus on Adam, Abraham, and Moses when we so obviously live in a different time? How can we apply these covenants to our lives under the New Covenant?

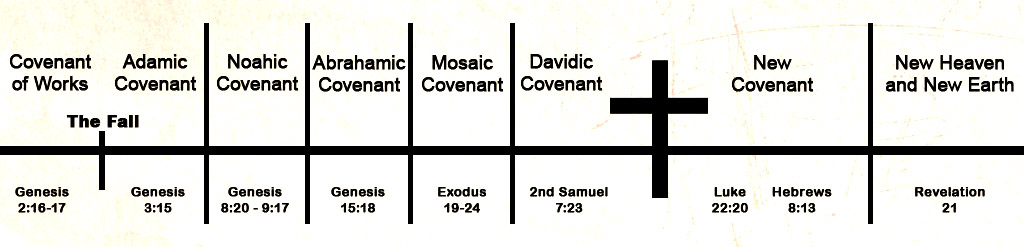

To answer this, we need a whole new way to think of how the covenants work. As we read through the Bible and see God make relational contracts with His people, it is easy to see these as replacing the former agreement. Whether this is because it didn’t work, new times require new details, or simply because progress demands more complexity, it is easy to imagine that every new covenant is an improvement over the last. This would simply place the covenants in a chronological order, creating time periods that correlate with each relationship, like this:

The problem with this is that it treats each covenant as its own stand-alone entity. As we talked about Sunday, God relates to us under more than one covenant. The various relational definitions help build for us a bigger picture, a single eternal covenant that ties them all together. This eternal covenant is the contract made between the three parts of the Trinity before the creation of the world; a single plan for why God creates, how God creates, and what creation exists for. While this conversation is not revealed to us, it is alluded to throughout the Bible, including Jesus’ High Priestly prayer in John 17, which says:

I glorified you on earth, having accomplished the work that you gave me to do. And now, Father, glorify me in your own presence with the glory that I had with you before the world existed. | John 17:4-5

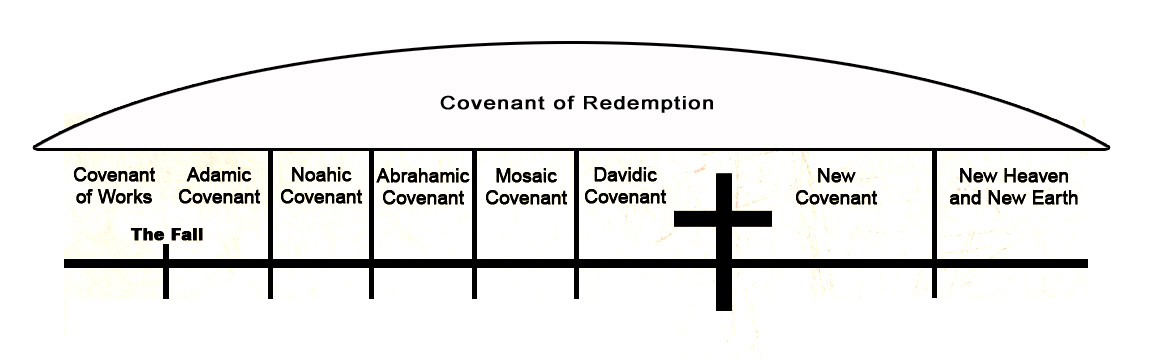

All of these covenants are pieces that fit into a larger, overarching covenant; something like this:

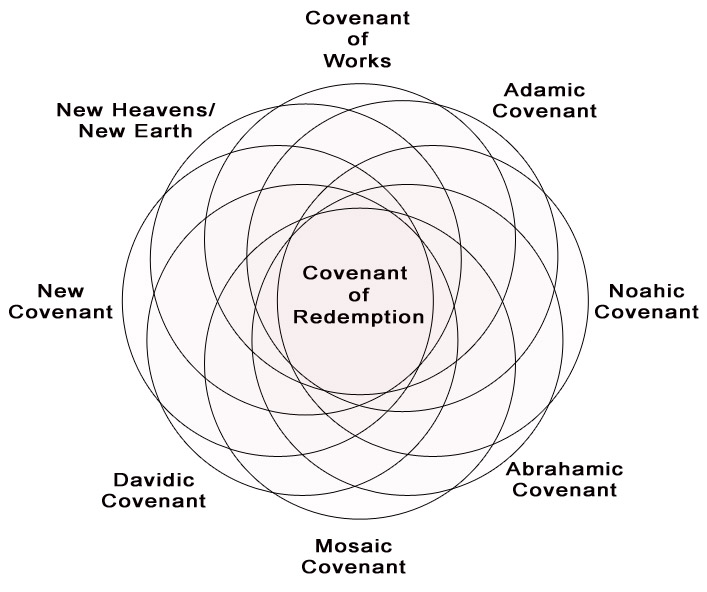

That still isn’t right, because it fails to do justice to the interplay between the covenants. While there are parts of the former covenants that we move on from (like the civil and ceremonial parts of the law), there is also a great deal that continues on as part of the eternal. While I have seen attempts to illustrate this relationship using arrows (lots and lots of arrows), I think a better way to view the covenants is as a Venn diagram (because Venn diagrams solve everything). Like this:

The idea here is that each covenant has an overlapping effect on the others, a part that is unique to the time and place that it was given, and an eternal portion that makes up the Covenant of Redemption. While we have the New Covenant, this does not do away with the unconditional promises of the Abrahamic Covenant, or the blessings and curses of the Mosaic, it simply magnifies them. Jesus fulfills these covenants by revealing Himself as the means by which God would fulfill both the requirements and the punishment simultaneously, as well as to provide us the ultimate motivation for obedience: the law is the designed pattern of a loving God for His creation. Though I did not mention the New Covenant explicitly, it is implied every time we connect the OT covenants to Jesus. Showing the overlap is acknowledging that God’s people live by God’s rules, no matter what time period they/we live in. The most important parts of the covenants are the parts that are eternal, not the parts that are exclusively ours.